303. The Traditional Plot is as old as the Greeks, maybe older.

a proven formula

Basically, the Traditional Plot is a formula, or THE formula for an exciting, interesting, engaging story.

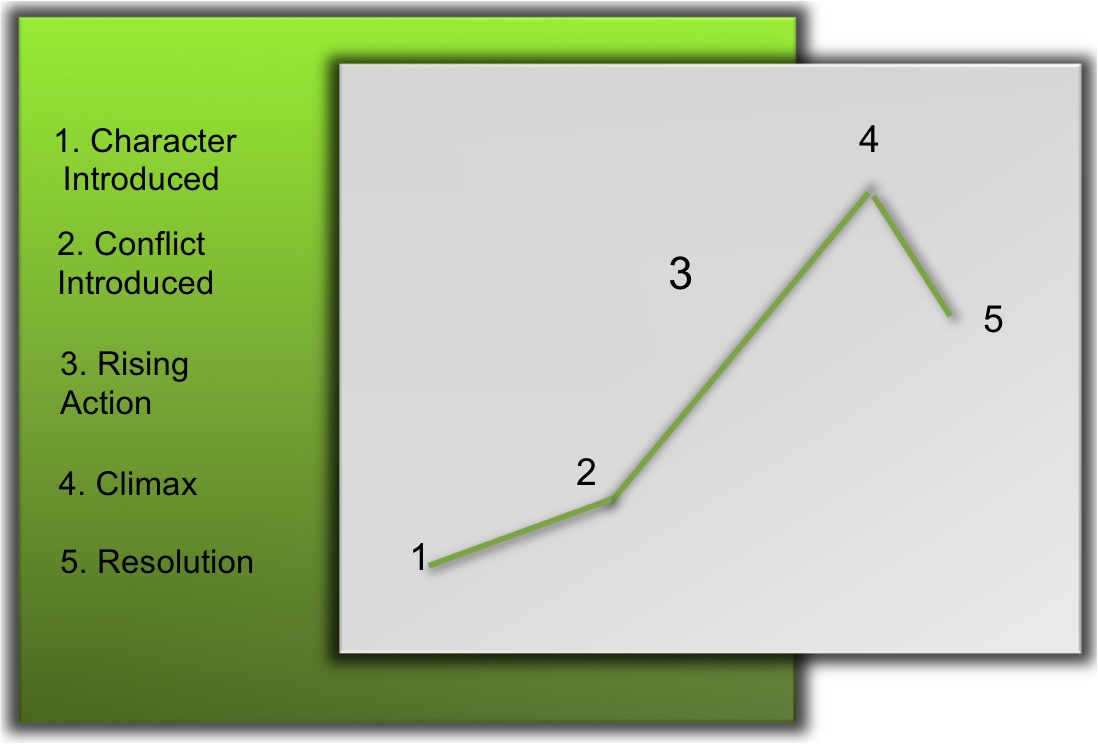

Story telling is an art. If you want to do it well, you look at other successful stories and you find the similarities between them. For thousands of years, people have been using The Traditional Plot formula to entertain each other. The Traditional Plot is the structure behind most of the stories and movies you know. You might not realize how ubiquitous it is, but it’s literally everywhere. Editors, filmmakers, sportscasters, song writers, fiction writers and biographers all know that if a story has a compelling structure, it sells, it entertains, it mystifies. The Traditional Plot just works. You can try to invent a new structure if you want to; no one is stopping you. But regardless of whether or not you want to use the traditional plot, you should know what it is. The chart to the right shows a linear representation of The Traditional Plot. But the best way to learn what this stuff means is to see it in action. In the text below, I will define one individual component from the formula, then show you that component in three different stories. Then I will compare the stories so that you can see how they are similar in their execution of each particular component. Note that “THE SET UP” and “Character flaw” sections are extra add ins that are relevant to the component being discussed, but they are not Traditional Plot components: 1. Character Introduction, 2. Conflict Introduction, 3. Rising Action, 4. Climax, and 5. Resolution.

Story telling is an art. If you want to do it well, you look at other successful stories and you find the similarities between them. For thousands of years, people have been using The Traditional Plot formula to entertain each other. The Traditional Plot is the structure behind most of the stories and movies you know. You might not realize how ubiquitous it is, but it’s literally everywhere. Editors, filmmakers, sportscasters, song writers, fiction writers and biographers all know that if a story has a compelling structure, it sells, it entertains, it mystifies. The Traditional Plot just works. You can try to invent a new structure if you want to; no one is stopping you. But regardless of whether or not you want to use the traditional plot, you should know what it is. The chart to the right shows a linear representation of The Traditional Plot. But the best way to learn what this stuff means is to see it in action. In the text below, I will define one individual component from the formula, then show you that component in three different stories. Then I will compare the stories so that you can see how they are similar in their execution of each particular component. Note that “THE SET UP” and “Character flaw” sections are extra add ins that are relevant to the component being discussed, but they are not Traditional Plot components: 1. Character Introduction, 2. Conflict Introduction, 3. Rising Action, 4. Climax, and 5. Resolution.

THE SET UP

The Set Up can be considered both parts 1 & 2. This is the part of the story that “sets the reader up” or gives the reader all the background they need to follow the story.

The Traditional Plot: Part 1. Character Introduction

This is where you introduce the main character, his strengths and weaknesses, and the setting in which the story will take place. In picture books, this should be done as quickly and efficiently as possible because kids are impatient. A really good picture book will even hint at what’s called the internal problem. You’ll see what this means as you read the examples.

Look at the three Character Introductions below:

Once upon a time, there were three little pigs who went out into the world to seek their fortune.

Once upon a time, there were three little pigs who went out into the world to seek their fortune.

CHARACTERS: The Three Little Pigs

SETTING: The World

All the Whos down in Who Ville liked Christmas a lot.

All the Whos down in Who Ville liked Christmas a lot.

But the Grinch who lived just north of Who Ville did not.

The Grinch hated Christmas, the whole Christmas season.

But don’t ask me why, no one quite knows the reason.

It could be perhaps, that his shoes were too tight.

It could be his head wasn’t screwed on just right.

CHARACTERS: The Three Little Pigs

SETTING: The World

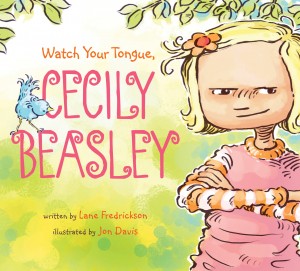

Cecily Beasley was never polite.

She never said, “Thank you,” or “Please,” or “Good Night.”

She tap-danced on tables. She cartwheeled in dirt.

And she wrote, “I won’t share!” on the front of her shirt.

CHARACTERS: Cecily Beasley

SETTING: Cecily’s Neighborhood

So let’s compare.

Character

All three stories have given the reader a good, solid character, or two (or three). In the case of all three stories, we have an advantage as a reader because the titles all give us the names of the main characters. Obviously, this part isn’t rocket science.

Setting

The Three Pigs’ setting is a little vague, but that’s okay because kids only need specifics if the setting is unique. The Grinch is the only story with a fantastical setting, and we have a solid name for this setting, Who Ville. And it’s tied to the characters, the Whos. One advantage of picture books is that the setting is going to be obvious because there are um, you know, pictures. Cecily’s setting is going to be the default world of Cecily, a world like every kid’s own world.

CHARACTER FLAW

Look closely at both The Grinch and Cecily. We got some extra information in these first few lines—and that’s always good. Both Cecily and the Grinch are flawed. The Grinch doesn’t like Christmas and that’s just weird. Every kid alive knows there’s something wrong with a guy who doesn’t like Christmas—and his name is Grinch; it just sounds grumpy. As for Cecily, she’s not a good kid. Right out of the gate, we know she’s “not polite,” and she doesn’t share. Main characters in children’s books don’t always have flaws, it’s not necessary, but it adds a layer of complexity to a story. The Greeks called this the Hamartia, and it makes the ending a little more satisfactory when a character overcomes not just a problem, but also a character flaw. A character flaw can also be called the internal conflict, because it is something the character struggles with inside himself, but don’t confuse this with “the conflict” which can also be called the external conflict. A Traditional Story does not have to have an internal conflict, but it does have to have an external conflict. This is covered in more detail below. Also, the pigs’ flaws will be revealed a little later in the story. Hold on.

The Traditional Plot: Part 2. Conflict Introduction

The conflict can also be called the problem. Note that this is the external conflict, not the internal conflict. So the internal conflict is the character flaw and the external conflict is the problem that the character faces in the world. It makes sense because a personal flaw is something inside the person (internal) and a problem is something outside the person (external). The external conflict is usually just referred to as the conflict. This is the element that causes tension in the story, the thing that must be dealt with, or found, stopped, or avoided. A traditional story MUST have an obvious external conflict. There is a type of Children’s story called an “episodic” or “slice-of-life” story that does not have an external conflict. But this type of picture book is merely anecdotal. It needs some other hinge or base to build upon. Slice-of-Life stories are covered in section 304.

Look at the three Conflict Introductions featured below;

The three little pigs kissed their mother good-bye and proceeded down the lane where they spied a man carrying straw. The first little pig was in a hurry to play his flute so he bought the straw and built his house out of straw. The second little pig was in a hurry to play his fiddle so he built his house of sticks. The third little pig knew that the forest was full of wolves so he worked very hard and found enough bricks to build his house. As he was building his house, his brothers came by and made fun of him for being such a worrywart. Then they ran off to the woods to have fun. But when night came, the big, bad wolf came out.

In The Grinch, we learn about the Grinch’s too-small shoes and heart. We hear how much he hates the noise, noise, noise, and the toys, and the feast, “Roast beast is a feast I can’t stand in the least.” But mostly he hates the Christmas carols, “They’ll stand hand in hand and those Whos will start singing.” The Grinch’s problem is that he cannot stand to hear all the rejoicing that the Whos will engage in on Christmas day. “I must stop Christmas from coming.”

In Cecily, we hear the specifics of her behavior, most importantly, that she sticks her tongue out at people. Cecily even gets a warning: “If you do it too much then your tongue might get stuck.” The Greeks used oracles and fates to warn their literary heroes. And, like Oedipus or Macbeth, Cecily’s fate is borne out and her tongue gets stuck.

In Cecily, we hear the specifics of her behavior, most importantly, that she sticks her tongue out at people. Cecily even gets a warning: “If you do it too much then your tongue might get stuck.” The Greeks used oracles and fates to warn their literary heroes. And, like Oedipus or Macbeth, Cecily’s fate is borne out and her tongue gets stuck.

Okay, so let’s evaluate conflicts.

Conflict in The Three Little Pigs

In the Three Pigs, before we get to the main conflict, the pigs’ flaws are revealed, or at least the flaws of the first two pigs. These two pigs are both lazy and not willing to work hard enough to build a sturdy, safe house. This character flaw has another good Greek element: the foil. A foil is a character who somehow reveals or highlights either the flaws or virtues of the protagonist/main character. In this case, the first two pigs’ laziness contrasts the industriousness of the third pig. By seeing their folly, we can see the virtue of the third pig, his willingness to work hard. So now we know that the third pig is the main character (also known as the hero or the protagonist). We also learn that there is a wolf. Wolves are always bad, especially when you’re a pig (or any variety of livestock). The conflict is the wolf, or the danger that the wolf implies.

Conflict in How the Grinch Stole Christmas

The Grinch’s problem is pretty simple; he hates Christmas and Christmas is coming. He intends to stop it by stealing all the Whos’ stuff. He assumes that if he takes all their toys and their feast and their presents, there will be no Christmas. So his conflict is Christmas. But remember that the Grinch also has what is called an internal conflict, and that is his grouchiness, or Grinchiness.

Conflict in Watch Your Tongue, Cecily Beasley

In Cecily, we see her get a warning about her tongue getting stuck. This warning foreshadows the conflict. The conflict is that her tongue is stuck sticking out. Never good. But remember that Cecily also has what is called an internal conflict, and that is her very bad manners. An internal conflict can also be called a character flaw.

The Traditional Plot: Part 3. The Rising Action

The Rising Action is the part of the story where tension builds. The main character must engage the conflict in some meaningful way. This is often where you see the concept of THREE. There are often THREE ways in which the character faces the adversary or tackles the conflict. This is the place where the character usually fails a couple of times, or reaches milestones but not the ultimate goal.

Look at The Rising Action in the three stories below:

In The Three Little Pigs, the first little pig was at home getting into bed when he heard a knock on the door. “Little pig, little pig, let me come in,” said the wolf at the door. The pig refuses and the wolf blows down the house and eats the first pig. Then the same thing happens to the second little pig. There is a far less violent version of the story where the wolf blows down the house of the first pig who quickly runs to the house of the second pig where the blowing down is repeated and the first and second pigs run to the house of the third pig. Take your pick, the action rises the same in either story. The wolf then comes to the house of the third little pig and tries to blow down that house, which is made of bricks.

In The Three Little Pigs, the first little pig was at home getting into bed when he heard a knock on the door. “Little pig, little pig, let me come in,” said the wolf at the door. The pig refuses and the wolf blows down the house and eats the first pig. Then the same thing happens to the second little pig. There is a far less violent version of the story where the wolf blows down the house of the first pig who quickly runs to the house of the second pig where the blowing down is repeated and the first and second pigs run to the house of the third pig. Take your pick, the action rises the same in either story. The wolf then comes to the house of the third little pig and tries to blow down that house, which is made of bricks.

In How the Grinch Stole Christmas, the Grinch prepares his sleigh and his reindeer and all his wares and proceeds to Who Ville. As the Whos sleep, he steals all their Christmas stuff, including their presents, their decorations, and their food for the feast. He even seems to be caught at one point when Cindy Lou Who wakes, but he convinces her that he is just fixing a light on her tree. When he is certain he has taken all the things that make the Whos love Christmas, he packs up to take the stuff back to his lair convinced that Christmas has been averted and that the Whos will cry and lament for the entirety of Christmas day and he will not have to hear them rejoicing.

In Watch Your Tongue, Cecily Beasley, Cecily’s tongue remains stuck. A bird lands on it and builds a nest there, also laying some eggs. Her parents take her to the doctor, but he just tells her that the birds are a feisty variety and should be left alone until the eggs hatch. “There are surely more serious things one could catch.” She remains in her bedroom until she gets so bored she must take a walk. But when she goes outside, people start laughing at her. Other kids make fun of her. Then the birds hatch and they stick their tongues out at her. She is thoroughly humiliated.

In Watch Your Tongue, Cecily Beasley, Cecily’s tongue remains stuck. A bird lands on it and builds a nest there, also laying some eggs. Her parents take her to the doctor, but he just tells her that the birds are a feisty variety and should be left alone until the eggs hatch. “There are surely more serious things one could catch.” She remains in her bedroom until she gets so bored she must take a walk. But when she goes outside, people start laughing at her. Other kids make fun of her. Then the birds hatch and they stick their tongues out at her. She is thoroughly humiliated.

Okay so lets evaluate The Rising Action:

Rising Action in The Three Little Pigs

In this section the pigs are forced to face the wolf and it does not go well. The tension rises as the wolf confronts each pig. The materials used to build the houses are sequentially sturdier and this progression parallels the tension. Note the use of three.

Rising Action in How the Grinch Stole Christmas

The Grinch is the longest of the three stories we are looking at by far and the rising action section is rather long. We see the Grinch taking the Whos stuff and the tension is at a maximum when he is caught by Cindy Lou. This is an extra plot twist to keep the tension escalating and although it varies from the descriptions of all the things the Grinch steals, it is one of the best moments in the play because it conveys just how awful he is.

Rising Action in Watch Your Tongue, Cecily Beasley

The rule of THREES is actually at work in this story, but it is very subtle. Cecily appeals to her parents, then they appeal to the doctor, then she tries to wait out her predicament in her bedroom. The action rises steeply as she goes outside and finds that everyone is making fun of her, even the birds on her tongue seem to be ridiculing her.

The Traditional Plot: Part 4. The Climax

The Climax is the point in the story when all the building tension comes to a final and relevant release. The main character and the conflict are confronted in the most explosive interaction of the story. This is generally the most memorable and interesting part of the story. This is where something shocking happens that changes all the dynamics of the story in a way that cannot be reversed and the hero either wins or loses. Either way, the conflict ends.

Time to look at the Climax in each of our stories:

In The Three Little Pigs, the third pig is confronted by the wolf. The wolf begs to come in, threatens, and huffs and puffs beyond his previous output. But the house of the third little pig holds, despite the effusive efforts of the big, bad wolf. There is a version of this story where the wolf, in a last ditch effort to get the little pig, tries to climb down the chimney. But the third pig (plus or minus the brothers who may have run to his house after theirs were huffed and puffed), puts a pot of water on the fire to boil and kills the wolf (or just scalds him into a truce).

In The Three Little Pigs, the third pig is confronted by the wolf. The wolf begs to come in, threatens, and huffs and puffs beyond his previous output. But the house of the third little pig holds, despite the effusive efforts of the big, bad wolf. There is a version of this story where the wolf, in a last ditch effort to get the little pig, tries to climb down the chimney. But the third pig (plus or minus the brothers who may have run to his house after theirs were huffed and puffed), puts a pot of water on the fire to boil and kills the wolf (or just scalds him into a truce).

In How the Grinch Stole Christmas, the Grinch is trudging up the hill with all the Whos’ Christmas stuff when he hears them singing. He realizes that Christmas is not just an event, or a party, but a state of mind. The Whos are rejoicing without all their Christmas paraphernalia. Unlike the pig who avoided the wolf, the Grinch is not successful in his bid to stop Christmas.

In How the Grinch Stole Christmas, the Grinch is trudging up the hill with all the Whos’ Christmas stuff when he hears them singing. He realizes that Christmas is not just an event, or a party, but a state of mind. The Whos are rejoicing without all their Christmas paraphernalia. Unlike the pig who avoided the wolf, the Grinch is not successful in his bid to stop Christmas.

In Watch Your Tongue, Cecily Beasley, when the newly hatched baby birds stick their tongues out at Cecily, she is disgusted at their rudeness and lack of manners. Her feelings are hurt and she suddenly sees that she has made other people feel this same way.

In Watch Your Tongue, Cecily Beasley, when the newly hatched baby birds stick their tongues out at Cecily, she is disgusted at their rudeness and lack of manners. Her feelings are hurt and she suddenly sees that she has made other people feel this same way.

Okay, so on to comparing:

Climax in The Three Little Pigs

In this climax, we see the resourcefulness of the third little pig pay off. He has confronted the wolf and won. He is still alive and his house has proven sturdy so we know that it will be a safe place from now on. We have seen all the same tactics that worked on the two brother pigs fail. We have hoped and rooted for this pig to overcome the wolf and our wish has come to fruition. We are satisfied with this outcome. It was hinted at in the set up when we realized that laziness was to blame for the first two pigs’ choice of building materials.

Climax in How the Grinch Stole Christmas

This climax has a definite link to the internal conflict. The climax is the point when we know for sure if the character has successfully faced and overcome the adversary. But notice that unlike the third little pig, the Grinch has not been successful. He has not prevented Christmas from coming. Normally, this would lead to an unhappy ending, but the great twist in this story is that the Grinch is kind of, you know, a bad guy. It’s rare for a bad guy to be the hero and that is part of the genius of this story. We know about the Grinch’s too-small heart and when he is unsuccessful in his quest, his internal conflict is addressed. So we get a double climax where the Grinch’s flaw is addressed, his heart grows two sizes. So the more satisfactory climax is the resolution of the internal conflict.

Climax in Watch Your Tongue, Cecily Beasley

In this climax, as in How the Grinch Stole Christmas, There is an interaction of internal and external conflict. Not only do the eggs hatch, assuring us that Cecily is now free from the birds on her tongue, Cecily realizes just how awful she has been. The tension builds up to the point that the birds stick their tongues out at Cecily. But after that, we see mostly just a realization on Cecily’s part. Much like the growing of the Grinch’s heart, Cecily’s character flaw is overcome.

The Traditional Plot: Part 5. The Resolution

The Resolution can also be called the denouement. This is the wrap up, the finale, the last scene that assures us all is well (or not well in the case of a tragedy). This is the part that lets you know how things will go on in a general sense for the main character. There doesn’t have to be much to the Resolution in a children’s story.

A look at Resolution in our three stories:

In The Three Little Pigs, this is the part where you can either say that the three little pigs had nice big helpings of wolf stew and lived happily ever after, or you can have that alternate ending where the third pig found his two brothers inside the wolf’s belly and let them out and they all live happily ever after.

In The Three Little Pigs, this is the part where you can either say that the three little pigs had nice big helpings of wolf stew and lived happily ever after, or you can have that alternate ending where the third pig found his two brothers inside the wolf’s belly and let them out and they all live happily ever after.

In How the Grinch Stole Christmas, this is the part where the Grinch returns all the Christmas stuff and then sits down to eat Christmas dinner with the Whos, enjoying some roast beast.

In Watch Your Tongue, Cecily Beasley, this is the part where Cecily apologizes to Bernard and we shares a plate of cookies.

In Watch Your Tongue, Cecily Beasley, this is the part where Cecily apologizes to Bernard and we shares a plate of cookies.

Okay, so last comparison and you should be a master of The Traditional Plot:

Resolution in The Three Little Pigs

The important thing to notice here is “happily ever after” Remember that “happily ever after” all by itself is part of the idea of the Resolution. The pigs have handily learned their lesson that sloth will lead to a terrible death and will now never be slothful again. This type of story is called a cautionary tale, because there is a direct link between sloth and some bad event. The implication is that sloth will always lead to wolves at your door (or some such event) and that it should be avoided.

Resolution in How the Grinch Stole Christmas

We are assured that the Grinch’s heart has grown, but also that he is included in the Who celebration by the Whos who have accepted him into their world. A simple implied theme here is acceptance and one wonders if this is what the Grinch wanted all along. The Grinch was never part of the Whos world. He is not a “Who,” but a Grinch and the very differentiation of names speaks subtly but powerfully to the theme.

Resolution in Watch Your Tongue, Cecily Beasley

Watch Your tongue, Cecily Beasley has similarities to both the Grinch and the Pigs. Like the Three Little Pigs, Cecily is a cautionary tale; there is an implication that her stuck tongue is directly related to her bad behavior. If you behave badly, bad things will happen. But it is also like the Grinch in that Cecily’s internal conflict is resolved via the empathetic realization that her behavior can be hurtful. The Grinch and Cecily each have an epiphany about their actions, take a gamble on kindness, and are rewarded with inclusion.