201. Chasing the Rhyme: Trying so hard to rhyme that you settle for an inferior story

Chasing The Rhyme

The hardest thing about rhyming is not settling. Coming up with really great rhymes that fit seamlessly into your story takes time and when you settle, your story will suffer.

Adding Rhyme to a poem or story can make it lively and clever, but you don’t have to rhyme to publish or be respected. Actually, it’s highly UNfashionable to rhyme. Rhyming your poetry in grad school is the social equivalent of schizophrenia– you could talk to yourself in public and be cooler. The publishing industry is a little better, but there are many editors who won’t even look at rhyme because when it’s bad, it hurts to hear it.

Adding Rhyme to a poem or story can make it lively and clever, but you don’t have to rhyme to publish or be respected. Actually, it’s highly UNfashionable to rhyme. Rhyming your poetry in grad school is the social equivalent of schizophrenia– you could talk to yourself in public and be cooler. The publishing industry is a little better, but there are many editors who won’t even look at rhyme because when it’s bad, it hurts to hear it.

So don’t torture people with bad rhyme, it’s rude. Make sure that you are rhyming because you want to and because you’ve taken the time to learn to do it well.

Still in? Read on.

Think about this: There are thousands of ways to tell any given story. Every one of those thousands of variations has hundreds of possible rhymes. Unless you’ve revised the story a thousand times – there could be a better rhyme. Okay, so maybe a thousand is a really big number, but remember that the BEST possible story is the goal. If you want editors to publish your manuscript, if you want parents to buy your picture book, if you want kids to love your story, then don’t they deserve your best effort? And if that isn’t convincing, remember that somebody else out there wants to publish too, and if they worked harder than you did – who deserves to publish?

DON’T CHASE THE RHYME – CHANGE THE STORY

Revising takes time. But even the most talented poets spend hours and hours revising. Elizabeth Bishop took several years to write her famous poem “One Art,” and it’s only nineteen lines long. There are probably hundreds of tactics you can employ to help you revise a poem, but the most important factor in revision – is time. Take the time.

1. Get a rhyming dictionary or use a rhyming website

I use Rhymezone.com and I use the thesaurus at Dictionary.com. Sometimes if you can’t find a rhyme for one word, you can look up some synonyms and work from there.

2. Try longer sentences

The lines to the right are End Stopped. End stopped sentences begin and end on one Metrical line. A lot of beginners think that this is a requirement, but it isn’t. You don’t have to fit exactly one sentence to a line. You may even know this, but as you work, you may find yourself trying to find sentences that fit exactly to a line.

The lines to the right are End Stopped. End stopped sentences begin and end on one Metrical line. A lot of beginners think that this is a requirement, but it isn’t. You don’t have to fit exactly one sentence to a line. You may even know this, but as you work, you may find yourself trying to find sentences that fit exactly to a line.

(These lines are from Dr. Seuss’s I Do Not Like Green Eggs and Ham. Random House. First ed 1960.)

There’s nothing wrong with End Stopping, but if you change the length of a sentence, you might find that a different word falls in the rhyming position.

(These lines and the ones in the box below are from Mary Ann Hoberman’s The Seven Silly Eaters. Sandpiper. Reprint Edition August 2000. Illustrated by my dream artist, Marla Frazee.)

The sentences to the left don’t always end with the end of a line, but they end at the transition of clauses. The last three lines are technically one sentence, but there are three separate clauses contained in that sentence:

1. squeezing lemons… 2. mopping milk… 3. preparing more…

Notice that if the author needed to, she could have changed the order of the clauses within the long sentence.

1. While mopping floor… 2. She squeezed lemons… 3. Prepared more… OR

1. She prepared more… 2. While squeezing lemons 3. And mopping milk…

Anyway, you get the idea. Longer sentences give your story or poem some flexability and they actually make it easier to alter the story for a better rhyme.

3. Try Enjambing

Enjambment is when the line of poetry ends, but the sentence continues into the next line. In the box to the right, the second line starts off with one short sentence. Short sentences are another good option to remember when revising. But look at how the second and third lines contain enjambment. If you’ve been end stopping, enjambing is a great way to make a new word fall at the end of the line, the place where the rhyme is. Remember that enjambment breaks up the rhythm a little bit, and this can actually be considered a good thing.

Enjambment is when the line of poetry ends, but the sentence continues into the next line. In the box to the right, the second line starts off with one short sentence. Short sentences are another good option to remember when revising. But look at how the second and third lines contain enjambment. If you’ve been end stopping, enjambing is a great way to make a new word fall at the end of the line, the place where the rhyme is. Remember that enjambment breaks up the rhythm a little bit, and this can actually be considered a good thing.

![]()

A bouncy, predictable rhythm gives a story a silly effect. When you vary the sentence length (not the the Metrical Line length), your story or poem starts to lose its predictable, rhythmic effect and in turn, it begins to lose that playful, silly quality. So, for a more serious poem or story, this is a good thing; you want to vary the line lengths and use a lot of enjambment to lose that effect. But a funny children’s story or humorous poem still works well even if there is very little variation. Many children’s stories maintain a flawless, end stopped rhythm throughout despite the fact that this is really hard to do.

4. Consider Meter Without Rhyme

Many serious poets wrote with Meter, but only rarely rhymed their verse. Milton’s epic, Paradise Lost, uses Meter, but almost no rhyme. Anyone who has read Shakespeare knows that he only rhymed his verse when the characters were impassioned in some way. And he generally only used bouncy, end stopped sentences when characters were ridiculous or sarcastic. Again, rhyme can up the silliness factor, so you have to be careful how you use it for serious works.

5. Reroute

5. Reroute

This is actually the most important concept in revision because it applies to every revisionary tactic. All the techniques above and below could be considered some type of rerouting. The specific type of rerouting I’m talking about here has to do with taking the whole story or section in a new direction. Sometimes this involves getting rid of something you thought your story couldn’t live without. I was revising a story for an editor who wanted me to cut ten lines down to four

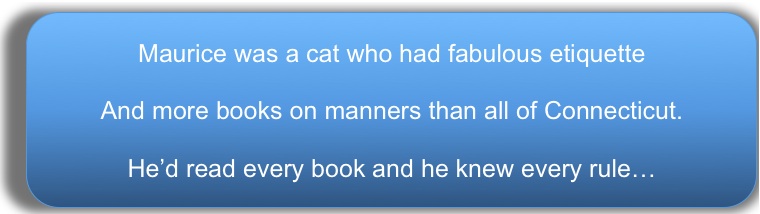

The next seven lines described Maurice’s manners more specifically, so they were pretty expendable. But since I needed that third line (shown above) to transition from the book idea in the second line, I was very limited in what the fourth line could say. AND I still had to transition into the action of the story. The key here is that in my head, I WAS CERTAIN that I needed those first two lines exactly as they were.

But I didn’t.

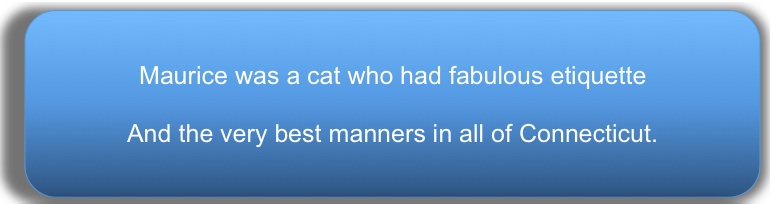

I wish I could say that I came up with this really obvious solution, but I didn’t. The editor did.

Ummm, duh. How stupid was I for holding onto the book concept anyway? I didn’t need to say he had books. Who cares if he had books? He had the best manners. End of intro. Sometimes rerouting just means rethinking all the choices you’ve already made.

6. Elision.

Elision is just a fancy word that means:

Skip some stuff

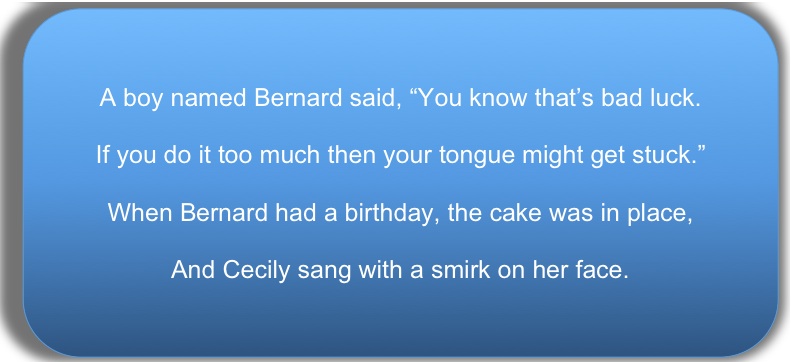

When writing, it’s easy to feel like you have to say everything that happens or list every mechanical action. But not only do you not have to, it’s better if you don’t. In this snippet from Watch Your Tongue, Cecily Beasley, by Lane Fredrickson (Sterling 2012) notice how much is left out between the first and second couplet:

The author hasn’t said that Bernard invited Cecily to his party or that she came or that the party is well under way or that the guests are singing “Happy Birthday” to Bernard. But the reader can guess all this. It might seem obvious when reading, but elision takes practice. You have to choose to say things in a way that allows the reader to infer or guess what has happened. In both picture books and poetry, you want to choose a specific instant and create an image of that instant that is vivid and concrete so that the reader can tell exactly what has been left out.

The author hasn’t said that Bernard invited Cecily to his party or that she came or that the party is well under way or that the guests are singing “Happy Birthday” to Bernard. But the reader can guess all this. It might seem obvious when reading, but elision takes practice. You have to choose to say things in a way that allows the reader to infer or guess what has happened. In both picture books and poetry, you want to choose a specific instant and create an image of that instant that is vivid and concrete so that the reader can tell exactly what has been left out.

Remember that there are thousands of ways to tell your story. Elision can be used over and over to cut down on length, or to alter the story to help you find a better rhyme.

7. Join A Critique Group.

A critique group will give you feedback on how your story sounds and give you suggestions on what things could use some work. Remember that you don’t have to change everything in the story that someone in your group suggests. But feedback is usually a good thing. WWW.SCBWI.org is the Society for Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators website and they can direct you to a group in your area. You could also start one of your own.

A critique group will give you feedback on how your story sounds and give you suggestions on what things could use some work. Remember that you don’t have to change everything in the story that someone in your group suggests. But feedback is usually a good thing. WWW.SCBWI.org is the Society for Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators website and they can direct you to a group in your area. You could also start one of your own.

8. Get a Professional Critique.

I offer critiques for a really reasonable price, but you don’t have to use my service. See Craft & Critique under Publishing on the navigation bar. There are several sites that will offer critiques.